Democracy in the European Union

1. Introduction

There has been an increase in peacekeeping and an introduction in peacebuilding operations after the end of the Cold War, directed by the United Nations and actively supported by Western democracies, where one of the aims was to 'aid in establishing democracy' in a nation (e.g. UNTAC and ONUSAL1) as a means for conflict resolution and prevention of recurrence of the conflict in the future, i.e. introducing democratic structures as a component for achieving positive peace. But what means democracy and what are democratic structures? And do 'we', citizens of the European Union, have the legitimate moral high ground to impose such a government system onto other peoples, in the light of the rising amount of criticism on the democratic deficit of the EU structures?

In this essay I compare ideas about democracy as surfaced in the 18th century, when modern forms of democratic structures were, either by revolution or gradually, introduced in Western countries, with the EU and the nations that make up the EU, and the validity/sustainability of claims to introduce democracy as a means to achieve lasting peace in non-Western nations.

2. Emergence and characteristics of modern democracy in Europe

Both Irish and Dutch citizens are convinced they live in a democracy, but their democratic structures in their respective nations differ widely, with both having valid arguments defending their system (see Appendix A-1 and A-2 for a brief overview). Moreover, the main players in Europe implemented a federal structure (Germany) or a bureaucracy (France). On top of, or should I say integrated within, these systems is the EU, with yet another version of more or less a democracy. Therefore, to clarify matters, I will start with the background that made the emergence of the idea of modern democracy possible, move on to the three different democratic forms, including the notion of a constitution and will discuss these points in the light of the structures of the EU. The EU, because in the current climate their power is probably greater than any individual nation-state within the Union.

2.1 2.1 One man, one vote

This slogan may look simple and straightforward, but there's more behind it than initially meets the eye: it implies that every single person, as an individual, counts; not the tribe, clan or caste one might belong to. First, you're human, then you're part of a society (Siedentop, 2000:189-214). Whereas Siedentop devotes a whole chapter to a link between Christianity, ethics and The Creation to explain that the basis of the concept of 'individual' lies within a Christian belief system (thereby implying other cultures may very well view things differently, which in turn would make it harder for democracy to materialize there) after discussing EU and democracy-related matters, Paine's (1791) writings about democracy started with this idea as a basis from which government may form:

"Every history of creation ... all agree in establishing one point, the unity of man ... that man are all of one degree, and consequently all men are born equal, and with equal natural right ... His natural rights are the foundation of all his civil rights." (emphasis in original) (Paine, 1791:29-30)

Paine continues with outlining the difference between natural individual rights and which of them are exchanged for civil rights, extending the idea of Freedom to [democratic] governments (1791:30-32):

"The fact therefore must be, that the individuals themselves, each in his own personal and sovereign right, entered into a compact with each other to produce a government: and this is the only mode in which governments have a right to arise, and the only principle on which they have a right to exist." (emphasis in original) (Paine, 1791:32)

On other words: government arises out of the people, not over the people. The individual may choose to pursue different values within a certain framework of law, which protects individual freedom, but also sets clear the boundaries of this freedom, applicable to every individual, i.e. a vision of equal liberty (Siedentop, 2000:201).

In comparison, or contrast, the emergence of the European Union. First supra-national cooperation after World War II was established with the European Coal and Steel Community (in 1951), restricted to one sector in the economy, extended to the European Economic Community (in 1957), with the signing of the Single European Act into the European Community, and finally after the Maastricht Treaty into the European Union (Vandamme, 1994:142-153). It is based in undemocratic cooperation based on economic advantages (with a hidden agenda of securing peace in the European region and, according to Siedentop (2000), the control of France over Germany), where the competences covered was extended gradually, i.e. moved from Member States to the EU, but the supranational structures put in place have not kept pace: the EU increasingly takes up the role of a government, but its structures aren't as democratic as its Member State governments2. Sure, the Assembly was renamed to European Parliament (EP) in 1979, and over time, most notably the Maastricht and Amsterdam Treaties, the EP acquired more influence, but is still run as a side-show. Did "individuals [citizens of the Member States] themselves entered into a compact with each other"? No. However, I have to note that citizens of some Member States were allowed to exercise their individual right in a referendum to join the EU or not and Irish citizens have the 'privilege' to vote on every Treaty, but this is more of an exception than the rule.

2.2 Constitution

Strictly, it can't be said that EU citizens entered into a compact with each other: a structure was set up and evolved into something that starts to resemble a European government, arisen over the people. However, according to the original ideas of Thomas Paine

"...government without a constitution, is power without a right." (emphasis added) (Paine, 1791:125)

and

"A constitution is a thing antecedent to a government ... which contains the principles on which the government shall be established, the manner in which it shall be organized, the powers it shall have... everything that relates to the complete organization of a civil government, and the principles on which it shall act, and by which it shall be bound." (emphasis in original) (Paine, 1791:33)

In addition, Siedentop (2000:81-101) further explains, by looking at recent history of nation-states and the concept of 'the individual', why constitutions are important, concluding that

"a written constitution can and ought to make a crucial contribution to self-awareness in any society with a state" (Siedentop, 2000:94)

and he notes that a constitution increases the confidence in the justices of public procedures, which in turn is "probably the single greatest guarantee of the durability of free institutions" (p96).

The EU has no constitution, only Treaties3, but as a result of increasing dissatisfaction with 'Brussels', i.e. the so-called democratic deficit, voiced by European citizens, the Laeken Declaration outlined part of the process by which a constitution of the EU may be established. Better late than never. Anon (2002) mentions the composition4, noting that "The Convention is composed of the main parties involved in the debate on the future of the European Union", Strangholt (2002a) lists contact details of the appointed and elected members (TDs, MEPs, civil servants), of which the chairperson is Valéry Giscard d'Estaing; the Economic and Social Committee, the Committee of the Regions, the social partners and the European Ombudsman are invited to attend as observers. Two months ago a first preliminary draft of an EU constitution was published by the Praesidium (2002), the 'executive' of the Convention, which received considerable criticism because, although several sections are not written in detail, it is heading in the direction of a federal superstate; common representation towards other states and common defence are some of the core issues in the draft for the United Europe, other issues involved are common citizenship and (unspecified) fundamental rights (Strangholt, 2002b). Bonde.com (Strangholt, 2002c) has published a 'Common Alternative' that is based on an EU of democracies instead, preferring simplified decision structures over practically un-traceable procedures, where over 30 different decision procedures have been identified (Bonde, 2002); Appendix B shows an example outlining the current decision structure of agricultural policies. They are publicly available (on the Internet), but is there public discussion? I doubt it. Moreover, it isn't even set in stone that, by the time there is a written final draft constitution, if all EU citizens will be allowed to vote on the constitution in a EU referendum, which, taking into account the previous paragraph, should be a minimum in trying to firmly establish EU democracy.

Reading the constitution proposals, I cannot withdraw from the idea that they build upon a not (officially or clearly) stated preconception of what type of democracy they envisage for the EU.

2.3 Democracy

To be able to 'read between the lines' in the constitution proposals, one should bear in mind the range of types of democratic structures that are discussed in the EU arena. There are three forms that differ in principle: democracy simpliciter, democratic government and a democratic society (Siedentop, 2000:48-63; Paine, 1791:119-1245 ). Simple democracy, as practiced in ancient democracies is impracticable for government of a state because of the size involved. A next step would be representative democracy:

"By ingrafting representation upon democracy, we arrive at a system of government capable of embracing and confederating all the various interests and every extent of territory and population" (Paine, 1791:120)

which, if true, could counterbalance arguments that large and populous countries like China, or an enlarged federal-type EU, are not suitable for democracy6. Siedentop refers to this type of democratic government as

"the discourse of 'classical republicanism' or 'citizenship', while the appeal for a democratic society or civil equality was associated with the discourse of 'civil society'." (Siedentop, 2000:51)

where citizenship from a social an intellectual setting which he considers pre-individualist ("to be free is to enjoy the privileges of citizenship"), the latter is grown out of the Christian Natural Law tradition, hence individualist in its assumptions where all people, not only the free, have a moral equality (Siedentop, 2000:53-57). Thereby suggesting that a democratic society goes a step further on the democratic ladder than Paine's elaboration on the res-publica (for example, Paine never mentions that women may have equal rights on a par with free men).

However, the very scale of a Western democratic society makes the active citizenship of classical republicanism (as opposed to resorting to passive consumerism) seem like a contradiction. To mix both types, one most likely will need to use the subsidiarity principle: delegate as much authority as possible to local and regional government to create the feeling of active involvement of citizens, and

"...federalism would be its natural extension. Federalism,..., makes it possible in principle, to adjust the claims of both citizenship and civil society" (emphasis in original) (Siedentop, 2000:63)

But delegating to the local level implies organization into communities, which poses problems in itself, as in not taking the individual (Siedentop, 2000) as the core entity on which all is built and creating institutionalized hierarchies which is "nothing less than a kind of apartheid that is not acknowledged as such" (Amin, 2001). In other words, federalism is not necessarily the ideal utopia either. In contrast, Shiva (2002) is convinced that "at the heart of building alternatives and localising economic and political systems is the recovery of the commons and the reclaiming of community" and thereby "reclaiming people's sovereignty and community rights to natural resources". Their opinions diverge further, in that Shiva is convinced that in a democracy, the (neo-liberal) economic agenda is the political agenda, whereas both Siedentop and Amin are convinced that capitalism is not closely related to the principles of democracy, though acknowledge they can interfere with democracy.

Looking at EU's history and structures, the two main players in shaping the cooperation are Germany and France, where the latter is more influential, which shows in the set-up of the EU: it is an extension of the moeurs the French bureaucratic democracy is used to7, unfortunately one where you have to

"...[proceed] on through an endless labyrinth of office till the source of it is scarcely perceptible,... It strengthens itself by assuming the appearance of duty, and tyrannizes under the pretence of obeying." (Paine, 1791:14)

This, even though the previous section of this paragraph indicated that to create a democratic society constituting of active citizens, federalism might be a more preferable option of organization in Europe.

3. Futures of the EU and evangelisation of democracy

Within the democratization debate in the EU, there are roughly three groups: the Europhiles preferring a bureaucratic solution (i.e. continuation of the existing process and more Treaties) or a federal European superstate (alike the USA), and the Euro-skeptics, also called the Euro-realists, who want less cooperation between the Member States for the time being, under the heading of the subsidiarity principle. A first aspect to decide upon is if one actually wants closer cooperation between the EU Member States: do we want a democratic EU or a Europe of democracies?8 Only after wide agreement on the answer, European citizens would need to look into the filling in the details on how to achieve whichever answer is chosen. At the moment of writing, partly because of the fact that the members of the Convention are predominantly Europhiles, tighter integration seems to be the direction in which the process is going. 'Thus' the question remains of continuation of Treaties, or adjust structures to facilitate a democratic federal European state. Based on the previous two paragraphs, a federal state would be the system that most closely matches the principles of democracy, i.e. the combination of a democratic government with a democratic society. The Praesidium's output heads towards federalism; Toulemon (1998) wrote within such a framework the changes that would be required to increase democracy within the EU. These ideas sound promising, but the main problem is, that it asks Convention members, many of them historically involved in shaping the current less-than-optimal EU decision structures, to re-design their child and give away power. Is it realistic that something like that will happen? Or is this Convention-stuff merely a diversion to silence criticism about the democratic deficit? Turning back the clock is not really an option and I do see the advantages of closer cooperation (enjoying the resulting harmonization regulations myself), and I certainly would like to see a redistribution of powers, but for the time being, I regret to admit that Europe rules us, and not vice versa.

Then, returning to the questions presented in the introduction: what means democracy and what are democratic structures, and do citizens of the European Union have the legitimate moral high ground to impose such a government system onto other peoples?

The idea of democracy finds its basis in Christianity, identifying the individual with his or here equal rights and liberties. Because of the increasing complexity of society, democracy simpliciter is not practicable and therefore has been superseded by a democratic government, or 'classical republicanism', and democratic society. A combination of the second and third form, the active involved citizen in a democratic society, could, in principle, be achieved by implementing federalism, based on a constitution. Siedentop sweeps some things together by claiming that

"... we come upon liberal constitutionalism as a surrogate for religion, as the latest frontier of European Christianity." (Siedentop, 2000:101)

This implies that when the EU wants to 'introduce democracy' in previously warring nations in order to achieve lasting, positive peace, it actually may not do so, nor is there a guarantee that a democratic system will work: not all societal structures see a human being as a first and then the individual as a group member to identify him/herself. Democracy brings with it the concept of the individual, which may very well go against age-old societies. Moreover, it could be interpreted as imposing Christian ethics onto them, in turn creating a sense of a hidden form of imperialism. Besides this, neither the EU, nor the USA for that matter9, currently follows the core ideas of democracy in practice as outline in the previous chapter.

Nevertheless, Toulemon (1998:129) insists that the EU offers a model and example of regional cooperation for organizations like NAFTA and MERCOSUR. On the other hand, Ruhana Padzil10 looked down upon the democratic systems of the Western nations/organizations, because elected candidates seem to be more concerned by short-term vote-winning than with long term progress of their own region. She claimed, that if elected representatives were in place for much longer than 4-5 years, they will need to focus on long term improvements instead and "sometimes it is just better for the people being ruled than when each individual wants to rule for him/herself'".

Personally, I'm reluctant to go down the road of cultural relativism as an argument for not promoting democracy, because I do think it is a fair system (well, at least in principle; besides, a half-hearted attempt for a democratic system is still better than e.g. a dictatorial regime). Secondly, I'm of the opinion that we, citizens of the European Union, must at least minimize the democratic deficit present in the EU and continue, of not seriously speed up, the democratization process in order to increase legitimacy in advocating democracy as a fair system to diminish the possibility of (recurrence) of war.

4. Conclusions

The idea of modern democracy, a democratic government and a democratic society, has its roots in Christian ethics of the natural (birth) rights of the individual. Comparing these ideas with the current system of the EU, the EU falls short on a constitution, on which a government ideally should be based, as well as the decision structures within the EU, carried out by mostly unelected, hence unaccountable, 'representatives'. Because of different backgrounds of its Member States, with each their unique implementation of a democracy, it will take considerable time to harmonize this and address the democratic deficit appropriately. Openly acknowledging this democratization process, the EU may advocate democracy as a fair government system, taking into account the 'baggage' of Christian heritage, but ought not to be surprised if not all nations and peoples of the world share the same level of enthusiasm for democratic values.

Rest me to mention that despite the sub-optimal structures and decision procedures of the EU, we do live in relative peace within the EU since WWII that may be, at least partially, contributed to the improved cooperation between the Member States, which has facilitated mutual understanding.

Notes

1. UNTAC = UN Transition Authority in Cambodia; ONUSAL = UN in El Salvador.

back to text

2. Commissioners are appointed, the Commission entertains the sole right of initiative, day-to-day activities of the Council (of Ministers) are carried out by unelected civil servants, where the ministers of Member States join horse trading during intergovernmental conferences (Bonde, 2002), elected MEP have a say on 5% of the total budget and on certain other topics approval voting rights; further, Mancini (2000) is proud of the judicial activism (read: 'dictating new laws') by the Court of Justice over the past 40 years to press the EU for legislation. See Keet (2001) for more detail on the composition of the involved bodies.

back to text

3. Judge Mancini (2000:1-50) discusses the validity/working of the treaties from the viewpoint of the EU Court of Justice, indicating "the Court has sought to 'constitutionalize' the Treaty, that is to fashion a constitutional framework for a federal-type structure in Europe" (2000:2), which Bonde (2002) acknowledges as well ("four basic Treaties and many different protocols make up the constitution of the EU")

back to text

4. The EU has launched a website dedicated to the convention process at http://european-convention.eu.int with up-to-date, but not full, information.

back to text

5. Pain includes in referred section reasons why monarchy and aristocracy will never fit either three types of democracy in principle, whereas Siedentop discusses recent history in a more practical sense.

back to text

6. As briefly discussed during one of the lectures of 'Origins, development and resolution of conflict'.

back to text

7. I do not make a value judgment if it is 'good' or 'bad', but that it just is. Probably, if the Netherlands were the superpower within the EU, we likely would have considered the Dutch system good enough to be transported into the EU structures. After all, it's often easier to extend/expand existing structures, than to come up with an entirely new one.

back to text

8. A full discussion on the pros and cons of both positions is beyond the scope of this essay. See Bonde (2002) and Tonsberg and Bonde (2002) for an 'interested layman's interpretation' on this matter.

back to text

9. President Bush didn't receive a majority in the popular vote, and there's still a gray cloud over the vote rigging in a few States. Secondly, it's only the millionaires who can afford to run for the Senate or presidency, hence not 'open for all' who may have the capacity to lead the nation.

back to text

10. Ruhana Padzil is a MA Peace & Development student from Malaysia. Information form her presentation on human rights for the course "Origins, development and resolution of conflict" d.d. 4-11-2002.

back to text

References

Amin, S. (2001). Imperialism and globalisation. Monthly Review, Vol 53, Nr 2, June 2001. Date accessed: 18-12-2002.

Anon. (2002). Organisation - Composition of Convention. The European Convention. Date accessed: 29-12-2002.

Bonde, J.P. (2002). The Convention - on the futureS of Europe. 27-2-2002. Available online.

Bonde, J.P. (2001). Nice Treaty explained by Jens-Peter Bonde. EUobserver, 30 May 2001. Date accessed: 6-7-2002.

Keet, C.M. (2001). European Union. Date accessed: 6-1-2003.

Mancini, G.F. (2000). Democracy and constitutionalism in the European Union. Oxford: Hart Publishing. 268p.

Meester, G. (1994). De institutionele kant van het gemeenschappelijk landbouwbeleid. In: EU-landbouwpolitiek - van binnen en van buiten. Hoogh, J. de and Silvis, H.J. (eds.). Wageningen: Wageningen Pers. pp 36-50.

Paine, M. (1791). Rights of man. Toronto: General Publishing Company. Dover Edition 1999. 200p.

Praesidium, The European Convention. (2002). Preliminary Draft Constitutional Treaty. CONV 369/02, 28 October 2002. 18p.

Shiva, V. (2002). The Living Democracy Movement - The bankruptcy of Globalization. Transcend - World Social Forum. Date accessed: 12-11-2002.

Siedentop, L. (2000). Democracy in Europe. London: Penguin Group. 254p.

Strangholt, M. (2002a). Convention members contact information. Bonde.com, 10-10-2002.

Strangholt, M. (2002b). Giscard presents state constitution. Bonde.com, 28-10-2002. Date accessed: 29-12-2002.

Strangholt, M. (2002c). Draft proposal for a Common Alternative. Bonde.com, 6-12-2002. Date accessed: 29-12-2002.

Tonsberg, M and Bonde, J-P. (2002). A democratic EU or a Europe of democracies? 28-6-2002. Date accessed: 15-7-2002.

Toulemon, R. (1998). For a democratic Europe. In: The European Union beyond Amsterdam - new concepts of European integration. London: Routledge. pp 116-129.

Vandamme, J. (1998). European federalism: opportunity or utopia? In: The European Union beyond Amsterdam - new concepts of European integration. London: Routledge. pp 142-153.

Appendix A-1

Democracy in the Republic of Ireland

Comments:

- ROI organizes referenda when intending to change the constitution and for ratifying every EU Treaty

- An Taoiseach and ministers (Oireachtas) are first elected in their respective constituency

- Irish citizens and residents of the ROI (>3 yr resident) vote representatives in their home constituency, vote representatives in their County or City Council and vote for representatives in the European parliament per province.

- City/County Council members elect a mayor or chairperson

- Seanad members are partly appointed by An Taoiseach, partly elected by Daíl members (TDs) and partly by certain Irish citizen groups (e.g. particular academia)

- Candidates do not have to be member of a political party

- The President is directly elected by popular vote

Criticism from another democratic structure:

The constituency TDs in the Daíl may have the problem of 'regionalism' (instead of advocating what's best for the country), smaller parties do not have candidates in all constituencies, thus limiting choice, and during the last election only 22 out of 42 had a female candidate to vote for.

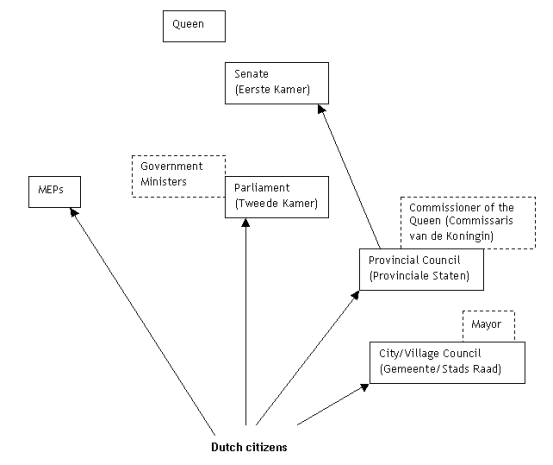

Appendix A-2

Democracy in the Kingdom of the Netherlands

Comments:

- Parliament and MEPs are elected based on national party lists (there are no constituencies, no transfer votes and no independent candidates), idem Provincial Council.

- It is possible that a minister was originally elected in Parliament, but when minister, he/she will leave parliament and the next person in the party list takes seat in his/her place. More often, ministers are appointed and will end their current job (e.g. a [former] mayor, judge, CEO).

- The Prime Minister normally is the first person on the list of the biggest party that make up the coalition government

- Members of the Provincial Council vote for the Senate candidates

- The Commissioners of the Queen and mayors are appointed via a select selection procedure based on party affiliation.

- There is no referendum, only a so-called 'corrective referendum': when the parliament votes for law A, some citizens want law B, then you'll have to collect 300,00 signatures, a referendum is organized, and if B wins, the Government and parliament must 'reconsider' and vote again on law A. There never has been a referendum in The Netherlands.

- Changes in the constitution are voted in Parliament and require 75% majority

Criticism from another democratic structure:

Each elected person is a 'country-wide representative' and cannot be held responsible by a group of citizens, construction of the party's list of candidates is based on favouritism by the party committee, the non-existence of referenda, appointed (thus not directly accountable) ministers, the monarchy (the Queen has more rights to intervene in politics and voice her opinion than the Irish President).

Appendix B

Structure of the decision procedure in EU agricultural policies

Source: Translation of Table 4.1 in Meester (1994:44)

The Amsterdam Treaty provided more rights to the European Parliament, but not on agricultural policies. The Nice Treaty was more concerned with changes from unanimity into qualified majority voting (Bonde, 2001).

This is an essay written as part of the course IL5052 - Origins, development and resolution of conflict, Department of Government & Society, University of Limerick, Ireland. Because a word limit was set, certain aspects did not get the attention they deserved; I intend to write more at a later date.